What Makes a Gay Restaurant So Special?

They've brought a whole lot of warmth and magic to American culture.

Hi! We don’t live on Substack anymore, but will occasionally be posting here to remind you to visit us at our new home. You can sign up for a membership or a free subscription, here.

A bad date, a satisfying meal, the promise of sex: That’s what happens, or used to happen, at gay restaurants like the Melrose.

Located at the corner of Melrose and Broadway, the Melrose was a gay restaurant that didn’t look gay, not right away. The booths and chairs were upholstered in shades of avocado and russet. I knew at least one of the servers was gay, but he was in his forties and partial to bushy mustaches and sensible knit pullovers, not busy midriffs and leggy rainbow-colored short shorts like servers at the glittery drag brunches that had gotten popular around town. There were no puns on the menu about buns or kielbasa, though if there had been, nobody would have been offended.

The Melrose was a gay restaurant because gay people made it one. It was where older gay couples sampled each other’s roast beef and mashed potato specials without asking first, as across the dining room, a four-top of butches feasted on chunky patty melts and audibly crisp chicken fingers. I once watched a table of loud-mouthed drag queens scarf down platters of grease-soaked bacon-and-cheese potato skins at two a.m. after they’d taken their bows at Foxy’s or Berlin, two of my favorite gay clubs that are now just memories. During weekend brunch hours, the Melrose transformed into the dining equivalent of a hopping gay bar, but with egg-white skillets and the roar of gossip instead of overpriced Cosmos and the thump of Chicago house music.

I was a Melrose regular. I ate there several times a week after midnight on my way home from my first journalism job, as the night-shift web producer at the NBC station downtown. If I couldn’t sleep, I’d go to the Melrose and read a book over a gooey grilled Cheddar on rye with fries, followed by a slice of warmed blueberry pie bearing a scoop of vanilla ice cream the size of my fist. Sometimes, I ate at the small counter to watch the cooks hustle, untempted by gay apps like Grindr or Scruff because they didn’t exist. I lived a few blocks from the Melrose, which is how, on one chilly winter morning circa 1999, next to me in bed was the same otter—the scrawny and extra-hairy type, my favorite—from the night before, who’d looked at me with a coy smile when we got up to pay our bills at the same time.

Melrose meals were within my modest budget and, most important, delicious, far better than typical greasy-spoon fare, thanks to cooks who knew their way around a hot grill and didn’t skimp on size. The menu rarely changed. Like most diners, it emphasized breakfast, which is why the dining room always smelled of syrup and sizzle, like maple butter melting on hot links. My go-to meal, no matter the time of day, was the chubby broccoli-and-Cheddar omelet, made with eggs so expertly fluffed, each forkful went down like chiffon. Without fail, it arrived at my table oozing pylon-orange cheese and snuggled against a heaping hill of humble buttery home fries. No Melrose meal was complete for me without a cup of its signature homemade sweet-and-sour cabbage soup—a tangy fusion of chunky tomatoes, vinegary broth, and thick-cut pieces of cabbage hugged by dill sprigs. A tall glass case near the front door was illuminated from within to show off fancy layer cakes and homey fruit pies. My favorite dessert was a squat sun- dae cup filled with creamy rice pudding, with a tall wig of whipped cream that the server dusted with cinnamon à la minute.

Location helped make the Melrose gay. It was an avenue over from Halsted Street, the blocks-long Boystown strip that bustled nightly with party people promenading between bars, nightclubs, and Steamworks, the neighborhood’s big and busy bathhouse. Many of the diners who frequented the Melrose were white gay men who could afford to live in gentrifying Boystown—Gen Xers like me who spent their twenties in Chicago working, sleeping around, and otherwise coming of age. Before gay life went digital, we learned where to party and eat from newspapers and bar guides that the Melrose and other local businesses stacked high near their entrances. During the summer, the Melrose was a popular spot for Cubs fans headed to and from nearby Wrigley Field—my way of saying that straight people ate there too. Not once did I see gays and straights clash at the Melrose, even during brunch when gay men cranked up the dining room to inferno levels of flaming. The only time I saw someone kicked out was for being drunk and belligerent, not for being gay, or homophobic.

In 2017, after fifty-six years in business, my beloved Melrose closed, for reasons that remain unclear. A year later, it was replaced by Eggsperience, a family-owned restaurant chain. Better that, I suppose, than some soul-sucking Chick-fil-A or a bank branch. But it’s not the same. While “I’ll see you at the Melrose” sounds gay, even a little chic, “Let’s go to Eggsperience” sounds phony, like ad copy rushed into print. It breaks my heart to think that, in being replaced, the Melrose might inevitably be forgotten. I left Chicago in 2001 and always go back to Lakeview when I visit, but not to Eggsperience. Pushing open those familiar glass doors would offer me nothing but a double whammy of crushing nostalgia: for a restaurant that’s no longer there and for an age—my twenties, that gay golden decade—that isn’t either. When I’m with my partner, David, and I see or hear the word “Melrose”—walking down Melrose Avenue in West Hollywood, for example—I’ll look at him with a sad face. He ate with me at the Melrose, too, and appreciates how much its absence breaks my heart.

In 2017, after fifty-six years in business, my beloved Melrose closed, for reasons that remain unclear. A year later, it was replaced by Eggsperience, a family-owned restaurant chain. Better that, I suppose, than some soul-sucking Chick-fil-A or a bank branch. But it’s not the same. While “I’ll see you at the Melrose” sounds gay, even a little chic, “Let’s go to Eggsperience” sounds phony, like ad copy rushed into print. It breaks my heart to think that, in being replaced, the Melrose might inevitably be forgotten. I left Chicago in 2001 and always go back to Lakeview when I visit, but not to Eggsperience. Pushing open those familiar glass doors would offer me nothing but a double whammy of crushing nostalgia: for a restaurant that’s no longer there and for an age—my twenties, that gay golden decade—that isn’t either. When I’m with my partner, David, and I see or hear the word “Melrose”—walking down Melrose Avenue in West Hollywood, for example—I’ll look at him with a sad face. He ate with me at the Melrose, too, and appreciates how much its absence breaks my heart.

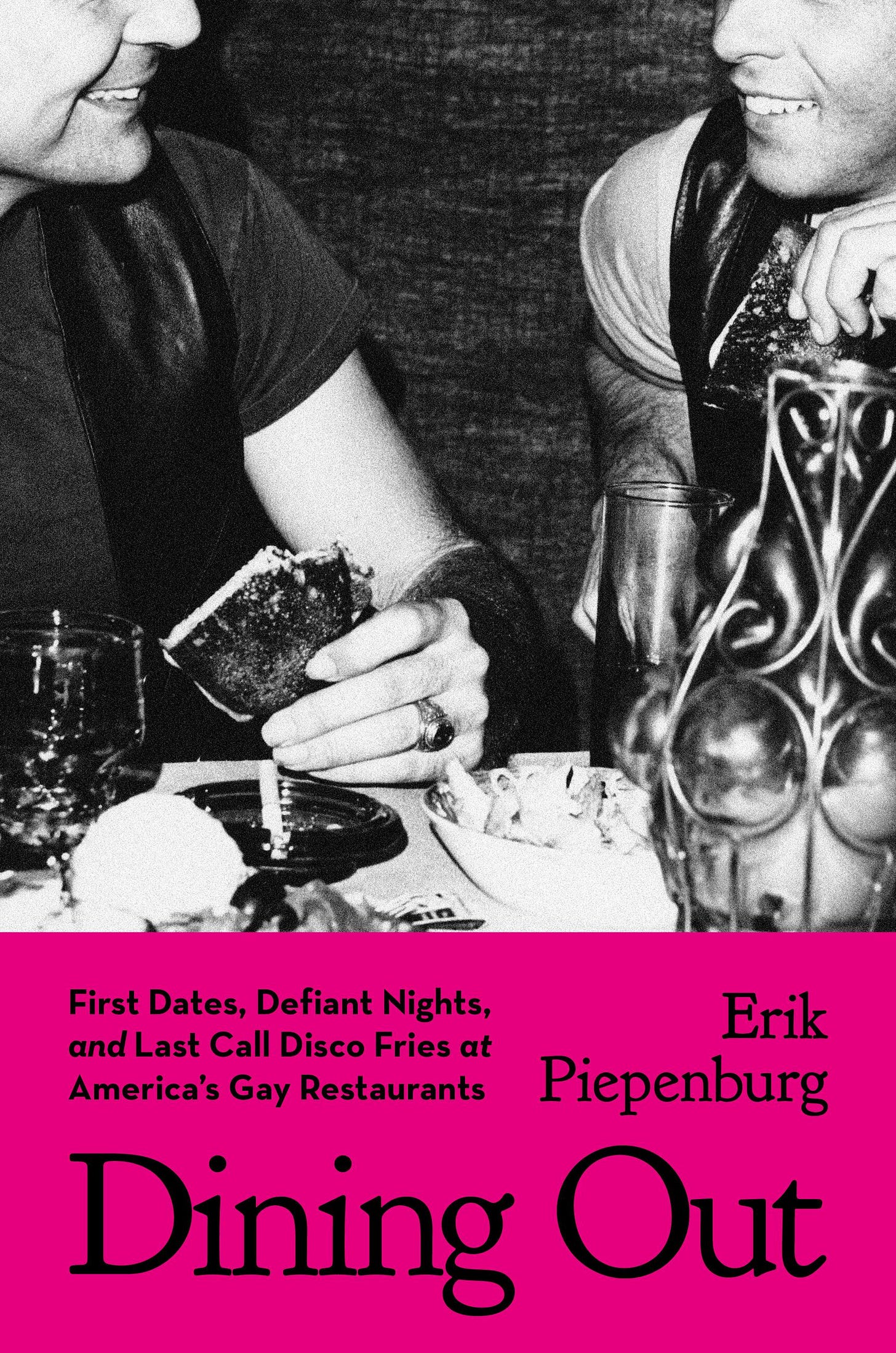

Adapted from DINING OUT: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants by Erik Piepenburg, published on June 3, 2025. Copyright © 2025 by Erik Piepenburg. Used by arrangement with Grand Central Publishing, a division of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.